The refugees who crossed the Mekong River into Thailand in the last days of America’s secret war traveled by night, their flashlights blinking on and off to help keep vision in the dark while hiding from Laotian soldiers.

From afar, the effect was that of fire flies floating above the water.

It’s an effect recreated on the large picture mural that runs the length of the entrance of “Vinai: Hmong Refugee Experience,” an interactive exhibit running through Jan. 1 at the Fresno Fairgrounds Commerce Building.

Ban Vinai was the largest and longest running refugee camp in Thailand, at one point housing more than 40,000 Hmong as they waited to be resettled. Many landed in cities across the United States, including Fresno.

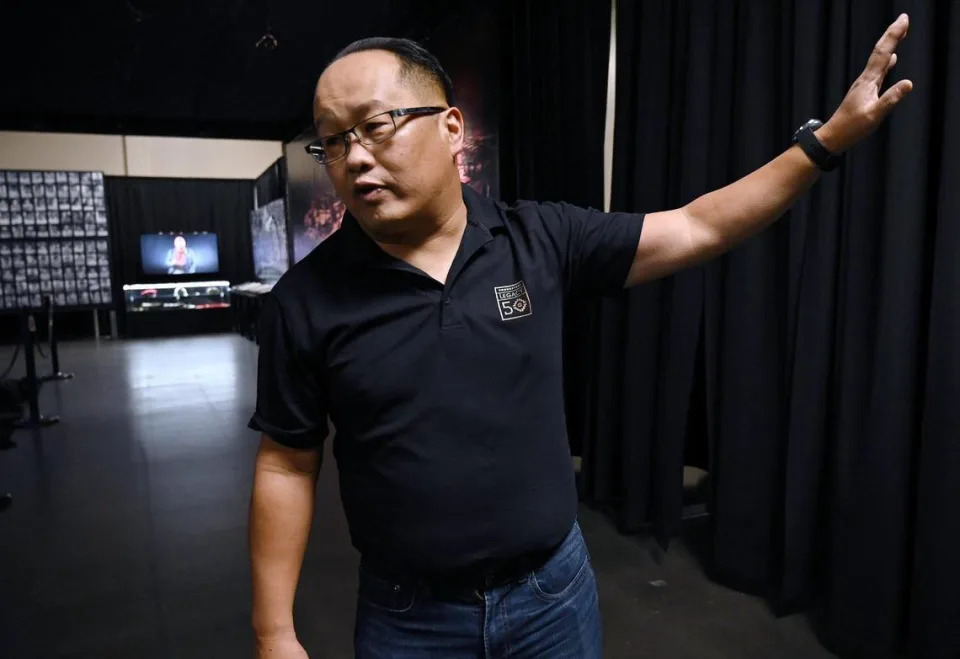

The exhibit chronicles the collective experience of those refugees, some of whom have suppressed those memories for more than 30 years, says Lar Yang, a co-founder of the Homngstory Legacy project and the exhibit’s producer.

“This is such a human story.”

Producers used a traditional hand-woven story cloth to create an animated video version that introduces guests to what would became the largest resettlement of non-European refugees in U.S. history.

From there, the exhibit is massive and meandering: a 25,000-square-foot installation piece of large-scale photos along with videos and ambient noises set around recreations of the camp.

There is a bamboo-made living space and an interview room, complete with official documentation and examples of the types of questions a refugee would be asked upon their intake at the camp.

Many documents are on display through out the exhibit; much of it declassified from the U.S. government. There are also maps of the Vinai camp (and others) drawn by aid workers, plane tickets and promissory notes. The refugees had to repay those costs.

An art gallery that runs the length of one wall, depicting the almost-mythical folktales that arose from the refugees’ journey to the camp, Yang says. For instance, parents who gave their children small doses of opium to keep them from crying. Many of those children died or suffered brain damage from the drug, Yang says.

If there is a centerpiece to the exhibit, it is a 32-foot-long wall of mug-shot style photos; 800 of them in total, each taken of a refugee just before their final departure from the camp.

In the faces, many of them just children at the time, you’ll find the future of the Hmong communities the eventually formed, Yang says. That includes the nation’s first Hmong mayor and the state’s first Hmong judge.

You will also find the full entire range of human emotions, Yang says.

“This is the whole plight of what war creates.”

The children in the photos throughout the exhibit are now in their 50s. What they remember of the experience is at risk of being lost when they are gone, Yang says.

Their children may not know about the refugee experience and might not even know how to ask.

So, while the exhibit has its share of dates and facts, names and numbers, Yang isn’t concerned with guests stressing over any of that, really.

“It means nothing,” he says, “if you can’t create a catalyst for people to want to know about their past.”

The Vinai exhibit is the first of four to be displayed over the next three years, culminating in 2025, the 50th anniversary of the first Hmong resettlement in the United States.

The ultimate goal is to create a permanent museum and digital archive for the project, and part of the exhibit is also a call for documents from the time, Yang says.

For example, the cassette tapes that many families used as a from of communication with relatives.

“This exhibit is kind of a learning exhibit,” Yang says.

“This is our capture system.”

Read the original article at Fresno Bee

Want to share your story? Email your story to [email protected]. You can remain anonymous.

Please report any errors and typos by emailing [email protected]